The dabbawalas or tiffin wallahs constitute a lunchbox delivery system that delivers hot lunches from homes to people at work in Mumbai (India). The lunchboxes (referred as Dabbas in Indian language) are picked up in the late morning, delivered either on foot, bicycles, carts, or railway trains, and returned empty in the afternoon. The unique thing about this story is the sheer volume and efficiency of the delivery management system. Between 175,000 and 200,000 lunch boxes are moved each day by 4,500 to 5,000 dabbawalas. This system has been subject of case studies by prestigious universities e.g., Harvard, Carnegie Mellon University, Indian Institute of Management and many more.

A Dabba in this context is a round metal container (made of steel or aluminum). They are also called Tiffin Carriers. Tiffin means light midday meal or lunch. Tiffin Carrier or Dabbas usually comes in packs of three containers stacked top to bottom, constrained with brackets on both sides with a locking mechanism at the top. In essence the Tiffin Carriers or Dabbas are used to packing and delivering midday meals, typically containing cooked lentils, vegetables and chapati (wheat bread) or rice. Tiffin Carrier term was introduced by the English (when they ruled India). So, this naming convention is not only tied to Mumbai, but it is quite common throughout India.

Origins

In the late 1800s, an increasing number of migrants were moving from rural areas to Mumbai from various parts of India. Fast food and canteens were not prevalent in those times. Workers left early in the morning for offices, and often had to go hungry for lunch. They belonged to different communities, and therefore had several types of tastes, which could only be satisfied by their own home-cooked meals. So, in 1890, Mahadeo Havaji Bachche started a lunch delivery service in Mumbai with about a hundred men. This proved to be successful, and the service grew from there.

The Efficiency

One of the keys to the dabbawalas’ efficient operations is the Mumbai Suburban Railway, one of the most extensive, complex, and heavily used urban commuter lines in the world. Its basic layout allows delivery people with bicycles and handcarts to travel short distances between the stations and customers’ homes and offices. The railway system sets the pace and rhythm of work. The daily schedule determines when certain tasks need to be done and the amount of time allowed for each task. For instance, workers have 40 seconds to load crates of dabbas onto a train at major stations and just 20 seconds at interim stops.

The tight schedule helps synchronize everyone and imposes discipline in an environment that might otherwise be chaotic. In addition, it provides clear feedback when performance slips. If a worker is late dropping off his dabbas at a station, his delinquency is immediately obvious to everyone, and alternative arrangements then have to be made for transporting his dabbas on another train. Problems can’t be swept under the rug and must be dealt with promptly.

A study by the Harvard Business School graded it “Six Sigma,” which means the dabbawalas make fewer than 3.4 mistakes per million.

The Making of Organization

Each dabbawala is required to contribute a minimum of capital in the form of two bicycles and a wooden cart (to move the dabbas from a sorting center to train stations). While on the job, the dabbawalas are required to wear clean clothes & shoes, and white caps (called Gandhi topi), making them easy to identify. They are largely uneducated: only 15% have attended junior high school. A handful are women, who typically perform administrative functions or special services (such as pickup or delivery at irregular times that command a higher fee).

The dabbawalas essentially manage themselves with respect to hiring, logistics, customer acquisition and retention, and conflict resolution. This helps them operate efficiently and keep costs low and the quality of service high. All workers contribute to a charitable trust that provides insurance and occasional financial aid—for example, when a worker needs to replace a bicycle that’s been stolen or is broken beyond repair.

Each dabbawala is an entrepreneur who is responsible for negotiating prices with his own customers. However, governing committees set guidelines for prices, which consider factors such as the distance between a customer’s residence and office and the distance between that office and the closest railway station. Because dabbawalas own their relationships with customers and tend to work in the same location for years, those relationships are generally long-term, and trusting.

Some of the workers with more than 10 years of experience serve as supervisors, or muqaddams. Every group has one or more muqaddams, who supervise the coding, sorting, and loading and unloading of dabbas and are responsible for resolving disputes, overseeing collections, and troubleshooting.

Logistics of the Delivery System

Unlike Deliveroo and Uber Eats – or India’s home-grown equivalents, such as Swiggy and Runnr – dabbawalas do not deliver restaurant food. Instead, they pick up home-cooked meals, mostly from the customers’ homes, and deliver them to their workplace in time for lunch. Each dabbawala take their dabbas to a sorting station, where they are sorted into logical groups, depending upon the destination distance that determines the delivery logistics i.e., on foot, bicycle, cart, or train. Dabbas that have to travel long distance are loaded onto wooden carts that are taken to a train station, loaded in the designated coaches of trains (usually there is a designated car for the boxes)

If the destination for some of the dabbas is at a walking distance from the sorting station, then designated carriers will carry their dabbas on their heads and deliver them at the destination. If the destination is up to five miles, then another set of designated carriers load their dabbas on the back of their bicycle and deliver them to the destination

For long distance deliveries (usually more than five miles), dabbas are loaded on carts and taken to the nearest train station. It is then taken by train to the station closest to its destination. There it is sorted again and assigned to another worker, who delivers it to the right office before lunchtime. In the afternoon, the process runs in reverse, and the dabba is returned to the customer’s home

Color-Coding System for Efficient Delivery System

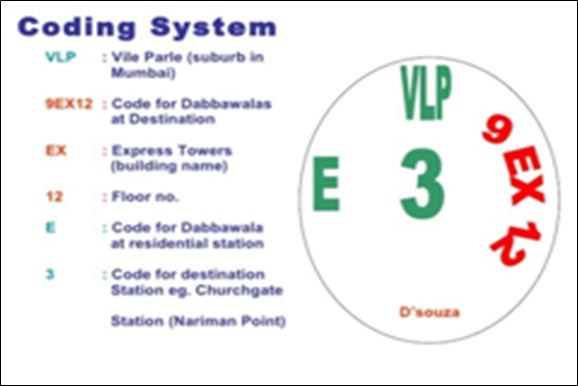

The coding system contains just enough information for people to know where to deliver the dabbas, but it doesn’t allow for full addresses. The dabbawalas, who run the same route for years but , however each dabba does contain the codes in order to maintain integrity of the system.

The lid of a dabba has the following key markings on it:

- Abbreviation for collection neighborhood with a bold number in the center, which indicates the neighborhood where the dabba must be delivered

- A group of characters on the edge of the lid: a number for the dabbawala who will make the delivery, an alphabetical code (two or three letters) for the office building, and a number indicating the floor

- A combination of color and shape, and in some instances, a motif—indicates the station of origin.

For long distance deliveries (usually more than five miles), dabbas are loaded on carts and taken to the nearest train station. It is then taken by train to the station closest to its destination. There it is sorted again and assigned to another worker, who delivers it to the right office before lunchtime. In the afternoon, the process runs in reverse, and the dabba is returned to the customer’s home

Customers supply small bags for carrying their dabbas, and the variation in the bags’ shapes and colors helps workers remember which dabba belongs to which customer.

The Economics

To perform their work most efficiently, the dabbawalas have organized themselves into roughly two hundred units of about twenty-five people each. These small groups have local autonomy. Such a flat organizational structure is suited to providing a low-cost delivery service.

The dabba delivery service is carried out six days a week, 52 weeks a year (minus holidays), but mistakes are extremely rare. Amazingly, the dabbawalas—semiliterate workers who largely manage themselves—have achieved that level of performance at very low cost.

Monthly fee (six days a week) for each dabba delivery is about one thousand Indian Rupees (about $12 US). Each month there is a division of the earnings for each unit, and they are distributed accordingly. It is estimated that a dabbawala is paid about 10,000 Indian Rupees per month (about $125 US in 2022). Dabbawalas are self-employed and belong to a union which guarantees a 5,000-rupee monthly income and a job for life.