Background

I read a book titled “Out of Istanbul” written by acclaimed journalist Bernard Ollivier. Heading east out of Istanbul on foot, Ollivier takes readers step by step across Anatolia and Kurdish-inhabited areas, bound for Tehran. Along the way, he met a colorful array of real-life characters: Selim, the philosophical woodsman; old Behçet, elated to practice English after years of self-study; Krishna, manager of the Lora Pansiyon in Polonez, a village of Polish immigrants; the hospitable Kurdish women of Dogutepe, and many more. We accompany Ollivier as he explores bazaars, mosques, and caravansaries—true vestiges of the Silk Road itself.

Ollivier’s journey, far from bragging about some tremendous achievement, humbly takes the reader on a colossal adventure of human proportions, one in which walking itself, through a kind of alchemy, fosters friendships and fellowship. His goal was to walk from Istanbul (Turkey) to Tehran (Iran) for 1524 miles. However, he got infected due to malnutrition, just a few miles away from Iranian border and had to be transported back to Istanbul via a medical transportation van and that experience was worse than walking itself.

Although I have read other books on Silk Road, Out of Istanbul is one of the very interesting and absorbing books about human adventure, grit, determination, and curiosity. One of the main objectives of this journey revolves around Ollivier’s passion to visit as many Caravansaries (traveler lodgings/inns before the modern-day motels and hotels) as he could. His account of these structures got me interested to do more research about Silk Road. In addition, the fact that he travelled through harsh weather, sometimes harsh humans, and animals, but all of that did not deter him from taking a ride along his journey from curious and kind locals. Reading of “Out of Istanbul” is the result of this blog. Reader dears, I hope that you will enjoy this post and explore other sources to know about this interesting history.

Persian Royal Road and the Age of Discovery

The Silk Road is neither an actual road nor a single route. The term instead refers to a network of routes used by traders for more than 1,500 years, from when the Han dynasty of China opened trade in 130 B.C.E. (Before Common Era i.e., before the birth of Christ that is termed as year 1) until 1453 C.E. (Common Era i.e., after the birth of Christ), when the Ottoman Empire closed off trade with the West. German geographer and traveler Ferdinand von Richthofen first used the term “silk road” in 1877 C.E. to describe the well-traveled pathway of goods between Europe and East Asia. The term also serves as a metaphor for the exchange of goods and ideas between diverse cultures. Although the trade network is commonly referred to as the Silk Road, some historians favor the term Silk Routes because it better reflects the many paths taken by traders.

The Silk Road extended approximately 6,437 kilometers (4,000 miles) across some of the world’s most formidable landscapes, including the Gobi Desert (in China and Mongolia) and the Pamir Mountains (Afghanistan). With no one government to provide upkeep, the roads were typically in poor condition. Robbers were common. To protect themselves, traders joined together in caravans with camels or other pack animals. Over time, large inns called caravanserai propped up to house travelling merchants. Few people traveled the entire route, giving rise to a host of intermediaries and trading posts along the way.

The Persian Royal Road ran from Susa, in north Persia (modern day Iran) to the Mediterranean Sea in Asia Minor (modern-day Turkey) and featured postal stations along the route with fresh horses for envoys to quickly deliver messages throughout the empire. Herodotus, writing of the speed and efficiency of the Persian messengers, stated that:

The closure of the Silk Road initiated the Age of Discovery (also known as the Age of Exploration, 1453-1660 CE) which would be defined by European explorers taking to the sea and charting new water routes to replace over-land trade. The Age of Discovery would impact cultures around the world as European ships claimed some lands and influenced by introducing western culture and religion and, at the same time, these other nations influenced European cultural traditions. The Silk Road – from its opening to its closure – had so great an impact on the development of world civilization that it is difficult to imagine the modern world without it.

One of the most famous travelers of the Silk Road was Marco Polo (1254 C.E. –1324 C.E.). Born into a family of wealthy merchants in Venice, Italy. Marco traveled with his father to China (then Cathay) when he was just 17 years of age. They traveled for over three years before arriving at Kublai Khan’s palace at Xanadu in 1275 C.E. Marco stayed on at Khan’s court and was sent on missions to parts of Asia never before visited by Europeans. Upon his return, Marco Polo wrote about his adventures, making him—and the routes he traveled—famous.

The Airport Fence for Dare Devils

Famous Cities Along the Silk Road

Cities grew up along the Silk Roads as essential hubs of trade and exchange, where merchants and travelers came to stop and rest their animals and began the process of trading their goods. From Xi’an in China to Bukhara in Uzbekistan, from Jeddah in Saudi Arabia to Venice in Italy, cities supplied the ports and markets that punctuated the trade routes and gave them momentum. After travelling for weeks on end across inhospitable deserts and dangerous oceans, cities provided an opportunity for merchants to rest, to sell and buy, and moreover, to meet with other travelers, exchanging not only material goods but also skills, customs, languages, and ideas. In this way, over time, many Silk Road cities attracted scholars, teachers, theologians, and philosophers, and thus became great centers for intellectual and cultural exchange forming the building blocks of the development of civilizations throughout history.

Here are some of the well-recognized cities along the Silk Road:

Aleppo (Syria), Alexandria (Egypt), Baku (Azerbaijan), Balkh (Afghanistan), Bamyan (Afghanistan), Bukhara (Uzbekistan), Beijing (China), Derbent (Russia) Ephesus (Turkey), Granada (Spain), Hangzhou (China), Herat (Afghanistan), Hamedan (Iran), Isfahan (Iran), Istanbul (Turkey), Jeddah (Saudi Arabia), Karakorum (Mongolia), Muscat (Oman), Palmyra (Syria), Samarkand (Uzbekistan), Tashkent (Uzbekistan), Tbilsi (Georgia), Tehran (Iran), Valencia (Spain), Venice (Italy).

The Role of Caravanserai Along the Silk Road

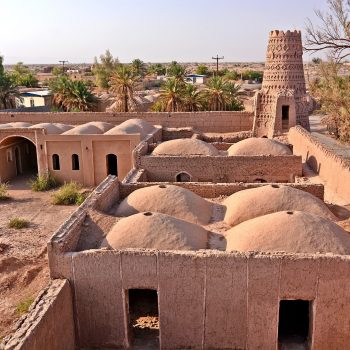

The journeys of merchants and their caravans along the Silk Road through the Middle East, Central Asia, and North Africa would have been much more difficult if not for the caravanserais (also spelled caravansary) that dotted those ancient routes. Variously described as “guest houses,” “roadside inns,” and “hostels,” caravanserais were buildings designed to provide overnight housing to travelers. Merchants and their caravans were the most frequent visitors. In furnishing, safe respite for guests from near and afar caravanserais also became centers for the exchange of goods and culture.

As traffic along the Silk Road increased, so did the construction of caravanserais. They were needed as safe havens—not just from extreme climates and weather, but also from bandits who targeted caravans loaded with silks, spices, and other expensive goods. In fact, caravanserais were built at regular intervals so that merchants would not have to spend the night exposed to the dangers of the road. They appeared roughly 32-40 kilometers (20–25 miles) apart—about a day’s journey—on the busiest Silk Road routes.

The design of these buildings also reflected their protective purpose. Often built just outside the nearest town or village, they were encircled by immense walls resembling those of a fort. Caravans entered through a high, massive gate that could be secured from within at night with heavy chains. A porter stood guard just past the gate, charged with safeguarding the persons, goods, and animals inside.

A Caravanserai Circa 400–500 CE

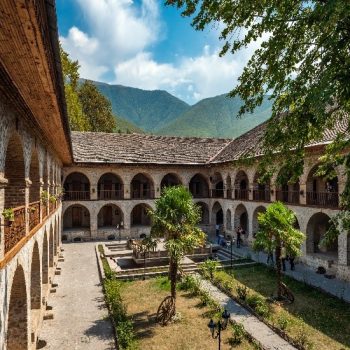

A Caravanserai Circa 1000 – 1100 CE

The interior of a caravanserai looked more like an inn than a fortress, however. A large ground-floor courtyard ringed with storerooms and stables for camels, donkeys, and horses would often have a corner for cooking fires as well. Small, unfurnished rooms for lodgers were found on the second floor. Some larger caravanserais also featured a bathhouse and prayer room. In the very beginning (during BCE) these structures were very crude with no architectural design taking place in construction. As the architecture and building techniques/technology improved, so did the design, strength, and attractiveness of those structures.

Most of the old caravanserais still in existence today are crumbling stone ruins, of interest only to historians and tour groups. In a very few places, especially near megapolis cities, some of these structures have been modernized and have become tourist attractions. In contrast, medieval caravanserais were lively seedbeds for globalization, resembling the modern city in the variety of people, languages, goods, and customs found within their walls. Travelers from East and West—speaking many different languages—traded stories, news, merchandise, and ideas while they mingled at these trade hubs. They sampled local cuisine and observed foreign etiquette. They learned more about Christianity, Islam, Judaism, and Buddhism from missionaries and scholars passing through. When they traveled on, they took much that was new and different along with them. The economic and cultural exchanges caravanserais made possible had far-reaching effects still seen today in the variety of languages, faiths, and cultures co-existing in this region of the world.

The Importance of Silk Road

It is hard to overstate the importance of the Silk Road in history. Religion and ideas spread along the Silk Road just as fluidly as goods. Towns along the route grew into multicultural cities. The exchange of information gave rise to new technologies and innovations that would change the world. The horses introduced to China contributed to the might of the Mongol Empire, while gunpowder from China changed the very nature of war in Europe and beyond. Diseases also traveled along the Silk Road. Some research suggests that the Black Death, which devastated Europe in the late 1340s C.E., likely spread from Asia along the Silk Road. The Age of Exploration gave rise to faster routes between the East and West, but parts of the Silk Road continued to be critical pathways among varied cultures. Today, parts of the Silk Road are listed on UNESCO’s World Heritage List.

Goods traded from West to East included:

- Horses

- Saddles and Riding Tack

- The grapevine and grapes

- Dogs and other animals both exotic and domestic

- Animal furs and skins

- Honey

- Fruits

- Glassware

- Woolen blankets, rugs,carpets

- Textiles (such as curtains)

- Gold and Silver

- Camels

- Slaves

- Weapons and armor

Goods traded from East to West included:

- Silk

- Tea

- Dyes

- Precious Stones

China (plates, bowls, cups, vases) - Porcelain

- Spices (such as cinnamon and ginger)

- Bronze and gold artifacts

- Medicine

- Perfumes

- Ivory

- Rice

- Paper

- Gunpowder

The Love of Silk

While many different kinds of merchandise traveled along the network of trade of the Silk Road, the name comes from the popularity of Chinese silk with the west, especially with Rome. The Silk Road routes stretched from China through India, Asia Minor, up throughout Mesopotamia, to Egypt, the African continent, Greece, Rome, and Britain. All aspects of Silk weaving were manual prior to the industrial revolution in modern world. Now majority of Silk production happens in modern factories, however there are still small pockets of manual Silk weaving in Southeast Asia.

Manual Silk Weaving

The northern Mesopotamian region (present-day Iran) became China’s closest partner in trade, as part of the Parthian Empire, initiating important cultural exchanges. Paper, which had been invented by the Chinese during the Han Dynasty, and gunpowder, also a Chinese invention, had a much greater impact on culture than did silk. The rich spices of the east also contributed more than the fashion which grew up from the silk industry. Even so, by the time of the Roman Emperor Augustus (27 BCE – 14 CE) trade between China and the west was firmly established and silk was the most sought-after commodity in Egypt, Greece, and, especially, in Rome.

The Silk Road Legacy

The greatest value of the Silk Road was the exchange of culture. Art, religion, philosophy, technology, language, science, architecture, and every other element of civilization was exchanged along these routes, carried with the commercial goods the merchants traded from country to country.

The closing of the Silk Road forced merchants to take to the sea to ply their trade, thus initiating the Age of Discovery which led to world-wide interaction and the beginnings of a global community. In its time, the Silk Road served to broaden people’s understanding of the world they lived in; its closure would propel Europeans across the ocean to explore, and eventually conquer, the so-called New World of the Americas initiating the so-called Columbian Exchange by which goods and values were passed between those of the Old World and those of the New, universally to the detriment of the indigenous people of the New World. In this way, the Silk Road can be said to have established the groundwork for the development of the modern world.

Original Author: Joshua J. Mark

Original Publication Website:

Food

Nature

Travel